By: Joe Donnelly

On Feb. 5, 2014, the world’s most famous wolf woke up somewhere along the Oregon-California border, very likely in the Cascade-Siskiyou National Monument, a landscape of Alpine forests and grassland valleys. For the better part of a year he had been making his home in this place where the Cascade, Klamath, and Siskiyou mountains converge.

It was cold that day, in the upper 20s or lower 30s depending on his altitude. Still, it was plenty warm for a gray wolf, which can sleep comfortably at 40 below. Known as OR7—the seventh wolf to be fitted by Oregon wildlife officials with a location-transmitting collar—the wolf likely rose, shook off whatever snow may have fallen on his coat overnight, and sniffed around for anything new and exciting. In the still morning air, he could pick up a scent from nearly two miles away.

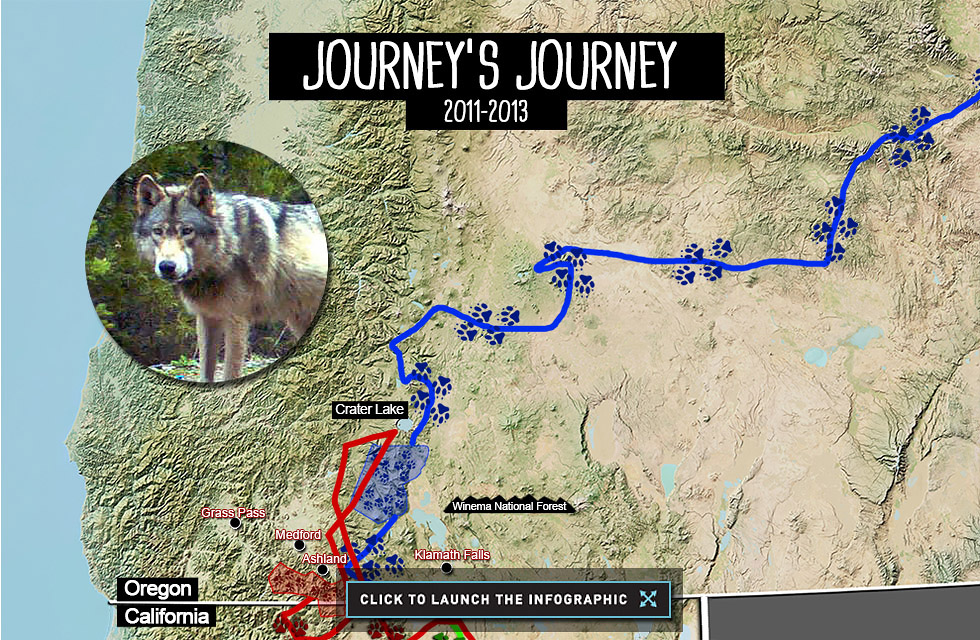

After getting a cool drink from a mountain stream, OR7 probably left his mark on a tree stump, just as he’d done thousands of times since setting out on the long, quixotic trek that took him from his birthplace in northeast Oregon and carried him over mountain ranges, across rivers and highways, and around the dangerous edges of civilization. Dispersing wolves tend to set up shop about 60 miles from their birth pack’s territory; OR7 was more than 500 miles from home. He’d been even further, deep into California, where he became the first wolf in nearly a century to take up residence in the state, staying for more than a year before settling down here in Oregon’s southern mountain ranges.

Since leaving home in September 2011, OR7 didn’t have much to show for his travels. Sure, he’d become an important symbol: His trek through lands that could form new wolf territories—lands conservationists would like to see protected and traditional Western lobbies would like to see exploited for hunting, ranching, and resource extraction—has added fire to the battle over the future of wolves in the West. It’s a battle framed at the extremes: Some wish to end livestock grazing on public lands altogether, others see the return of wolves as an ominous threat to be addressed by any means necessary.

And he had defied long odds. A lone wolf as far from a pack as OR7 was last winter has a life expectancy of about five years, and he would be five in a few months. His brother and sister had already been killed by humans. By surviving, OR7 revealed much about the meaning of state and federal endangered species acts, about the effectiveness of conservationist tactics in an era of severe stress on the environment, and, like the constant hum of a buzz saw in the distance, about who maintains the upper hand in the culture clash between the old West of ranching, logging, resource extraction, and hunting and the new West of coffee shops, art galleries, ecotourism, and conservation.

Continue reading the rest of the article by clicking here.

Story and Photos from: http://www.takepart.com/feature/2014/12/17/or7-wolf-journey-california-oregon-endangered-species?cmpid=tpdaily-eml-2014-12-17

You must be logged in to post a comment.